STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

If you’re expecting beautifully printed graphics on packaging to differentiate your product from the competition, think again. Before visual design creates a need in the consumer to interact with your product, the consumer recognizes color and shape. Having defined the parameters within which you are able to create in Part 1 of this series, the focus now shifts to defining; white-space, user-experience, materials, shape, and structure. Packaging & Dielines is also available as a Free Downloadable Resource to inspire new engaging structures with easy to follow dielines as you explore the possibilities of structural packaging design.

Understand that the parameters set in Part 1 are guidelines that define a client’s needs, limitations, and comfort zone, being well informed of the boundaries allow you to push beyond them. How far beyond those boundaries will depend on a risk reward trade-off, does ROI increase incrementally as you push beyond the established boundaries?

Here are 8 steps to get you started designing well informed packaging structures.

SKETCH

Start with broad strokes, never zero in on your first concept, it’s probably not as good as you think. Every project begins by having a clear understanding of the product/s to be packaged, that includes their weak points, weight distribution, product tolerances, and fulfillment method/s as defined in Part 1 of Packaging 101.

1) Create momentum in the ideation process by allowing yourself the creative freedom provided by sketching. There isn’t a specific number of sketches recommended, but you should strive for 20 – 30 concepts.

Each thumbnail sketch should address one or more of the goals set in Part 1. For example, mass market items with tight budget constraints require automation in production, as well as considering cost cutting materials, and processes. Streamlining assembly at fulfillment centers with pop-up features typical of auto-locking bases, simplex styled constructions, and built-in product inserts will also impact overall packaging budgets. Tight budgets do not mean that you overlook the end user experience, it simply means that understanding the end user will allow you to create an appropriate unveiling experience. Start exploring concepts with those cost cutting features, and evolve their unveiling processes until you have

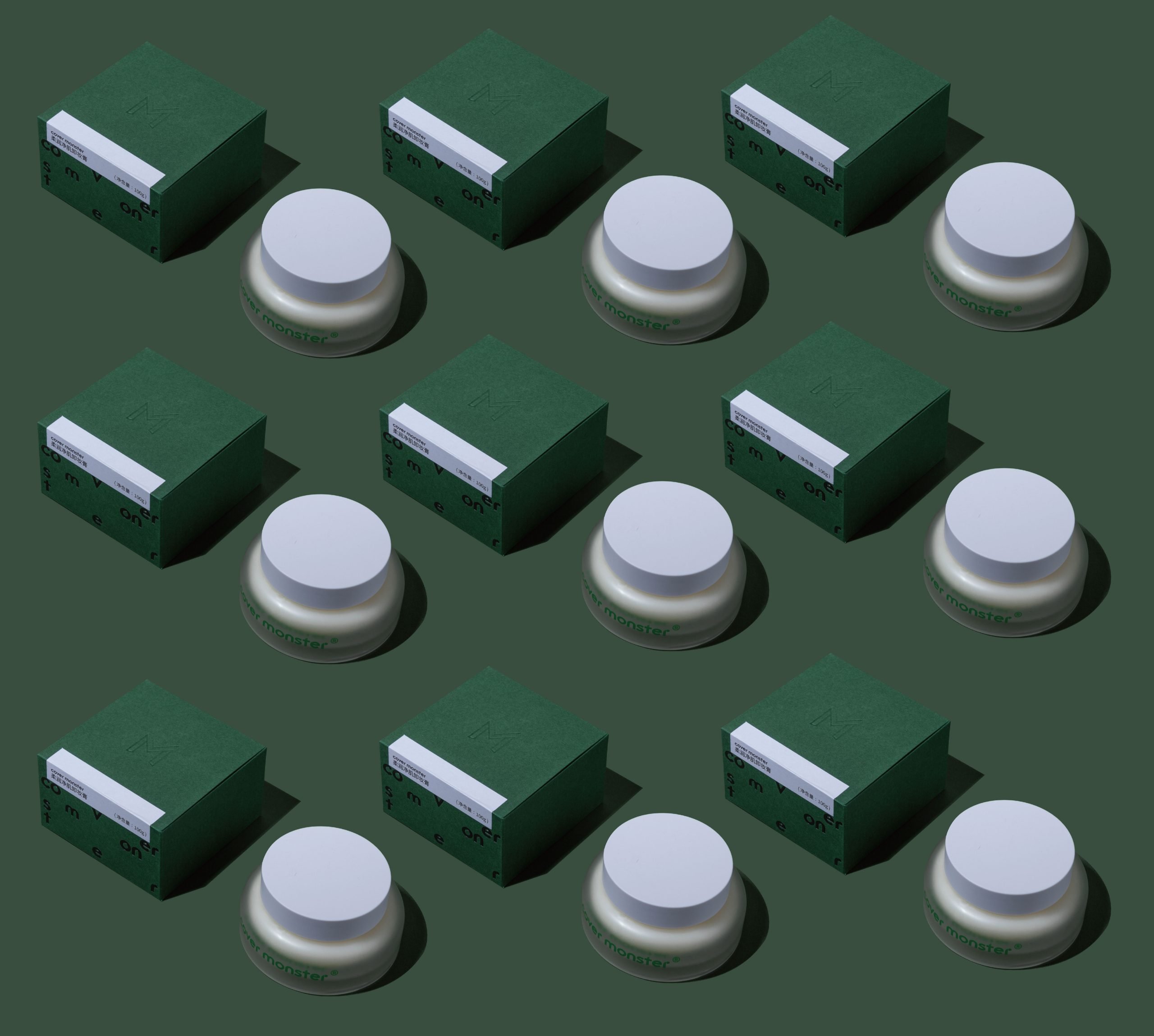

On the other side of the spectrum, luxury packaging focuses less on automated processes and more on unveiling and creating a tactile user experience through structural design and material selection. The unveiling processes is defined by the delayed product reveal that heightens anticipation, and delivers key signature moments at every user interaction. Read Top Ten Luxury Packaging Cues to explore luxury packaging further.

2) Exhaust all possible directions and push the boundaries of your established parameters.

t is time to edit. Editing means reviewing the pros and cons of each packaging structure, and evolving designs by incorporating the pros of the strongest concepts and solving for the cons into five powerfully concise structures. Structural presentation must address a brand appropriate user-interaction process that includes the initial point of contact, unveiling, returns, reusability, and end of life.

RAPID PROTOTYPE

Where great ideas are sculpted by failure.

Working with paper prototypes allows you to ideate as you build, finding innovative answers to hurdles encountered in rapid prototyping. This is not entirely possible in the Working Model phase as focus tends to shift from innovation to production quality, this tunnel vision experienced in creating working models is the reason the rapid prototype phase is crucial to innovation.

In the rapid prototype phase your goal is to push structure to support the product using a minimal amount of material, and create an intuitive unveiling experience for the consumer. The reason for minimizing the amount of material is that it allows you to design efficiencies in the process that yield less cumbersome structures. Structure has to follow function first by simplifying the needs of the pack, then you can begin altering your structure to create brand appropriate interactions in the design of the packaging.

3) Layout rough pencil dielines from which to build you paper mock-ups. These paper mock-ups allow weaknesses in the structure not visible in the sketch phase to present themselves and allow you to address them before you get too far in the design process. This phase also allows you to chip away at any excess material, create folds that interact with in-store lighting, or discover simple interactions that support the brand promise.

4) The benefit of rapid prototyping is how quickly structures reveal their weaknesses at this stage. Knowing the structure’s weaknesses you are able to sketch solutions to those hurdles presented by paper mock-ups, build new prototypes, and repeat as often as necessary. The goal of this iterative rapid prototype process is to pare your five structural directions down to two structural concepts that can be further refined into working models. Always test structures with a broad demographic to provide insight into how consumers will view, interact, and handle your structural design. Never work in a vacuum.

5) Take final measurements of products, paper mock-ups, shelving, and create your vector dielines. You can do this in your preferred software by scanning in your unfolded mock-up and applying measurements from fold to fold. Always work and label dielines based on internal dimensions, should materials change throughout the process it will only impact outer dimensions. Internal dimensions influence product fit and function, external dimensions do not.

WORKING MODELS

Review the two selected directions with the brand, fulfillment, and production to further refine the design into working models that can be tested for strength, interaction, and usability. Working models are representative of structure and define production specs that include materials and processes. Not everyone can envision your 3D concepts without having a fully working proto in hand, a working model also sets expectations from fulfillment to the final unveiling. The goal of this collaborative review of structure can be used to define key messaging opportunities in the consumer’s unveiling process as well as any production streamlining methods. Changes that happen often in this stage focus on fit, function, materials, and fine tuning interactions.

6) Build your working models in final production materials through the specified manufacturing procese in order to properly test strength, fulfillment, hand-feel, and the unveiling process. Work closely with your production team at this stage to confirm you are within production capabilities that meet budget, timeline, and quantity requirements previously set in Part 1.

7) Photograph and compare your structures under various lighting condition to replicate on-line, in-store, and at home experiences. Check structures in the shadows cast by shelves, or at the angled distances packaging structures present themselves in store aisles. Studying the packaging under various lights, angles, and distances may reveal flaws, or opportunities that can be exploited in the visual design phase. Lighting variations will also highlight how your package will look in different environments from boutiques to big box stores.

8) Incorporate test results into final structural drafts, update dielines, material selection, grain direction, and repeat the working model phase as needed.

In an effort to shed light on the subject of structure, I asked 2 packaging structural designers to share their process as well.

Mat Bogust of Think Packaging outlines his process:

1. Ask & Probe, where will it be sold? Retail/online/supermarket? what types of quantities?

2. Familiarize yourself with the product, hold the product, feel the product.

3. Ideate/Sketch/Visualize how it can be packaged, creating a 3D form and unfolding it in my mind then sketching the layout onto paper.

4. CAD! Starting with fittings and product protection, then working outwards to the panels based on how I wanted it to look and feel in step 3.

5. Sample. Hand cut and crease the proper materials to feel as if they are coming off of the production line, and editing along the way.

Andrew Zo the mind behind the Clifton ring case outlines his process:

1. Research

Look through the current packaging designs that are on the market. When I see a unique packaging, I will try to get a hold of it and tear the packaging apart to examine the dieline and learn how the unique structure is formed.

2. Ideation

After doing the initial research, I begin to brainstorm some possible ideas on paper.

3. Prototype

i prototype with paper and make quick models to test out my sketches. What I had learned in the research phase often informs me in this part as well.

4. Refine

After all the various testings, I will make a polished prototype. This prototype gives me a good understanding of what the final design could look like. It will also allow me to test out the unboxing experience now that I have a close to finish structure.

5. Dieline creation

Once I am satisfied with the prototype then I can translate it into a dieline.

Structural design is one of the least utilized tools today, regardless of being able to deliver powerful brand defining signature moments. These 8 steps, are meant to serve as a starting point to develop your own method of structural concept development. The steps outlined by Mat & Andrew are examples of how personal these processes can be. There is no right way, only what works for you. The goal is to push structures beyond generic forms, as away to support and convey the brand promise and not fade into a shelf of sameness.

Let me know how you have developed your process in the comment section below.

Evelio is the Creative Director of Design Packaging Inc., his reputation as one of the leading structural and visual packaging designers for international retail brands has led to successful collaborative partnerships with luxury brands spanning industries from fashion & beauty to wine & spirits. His extensive knowledge of processes, materials, manufacturing, and budgets, in addition to design, has led he and his team to become a trusted source in the ever-evolving world of retail.

Evelio’s co-authored book series Packaging & Dielines: The Designer’s Book of Packaging Dielines, a free resource in partnership with TheDieline.com continues his personal mission of supporting and building a global design community through collaboration and education.