The History of Plastic: Why Won’t Big Beverage Brands Ditch the Plastic Bottles?

By

Published

Filed under

By

Published

Filed under

This is the fourth and final part of our series, The History of Plastic. You can find the first chapter on the invention of throwaway living here and the second part on McDonald’s role in the single-use plastic crisis here, and the third installment on the theft of the recycling symbol here.

Walk into your nearest quickie mart, and you’ll see a wall of refrigerators packed with cold refreshments. No doubt, you’ll see a few rows dedicated to Pepsi and Coca-Cola, not to mention all of the drinks PepsiCo and The Coca-Cola Company produce (Dasani, Tropicana, Minute Maid, Gatorade, and oh so many more). Many of these will come packaged in a plastic bottle.

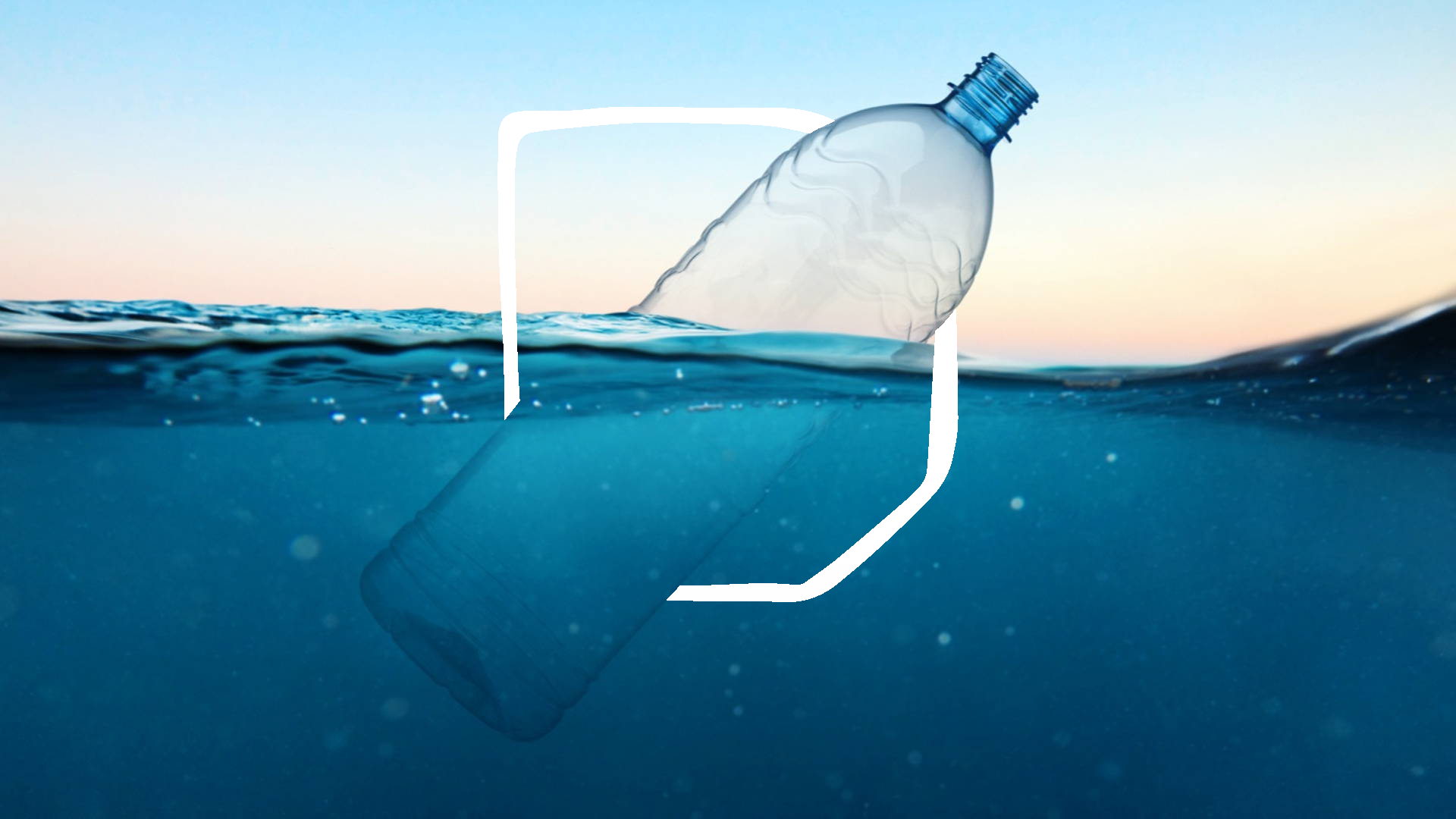

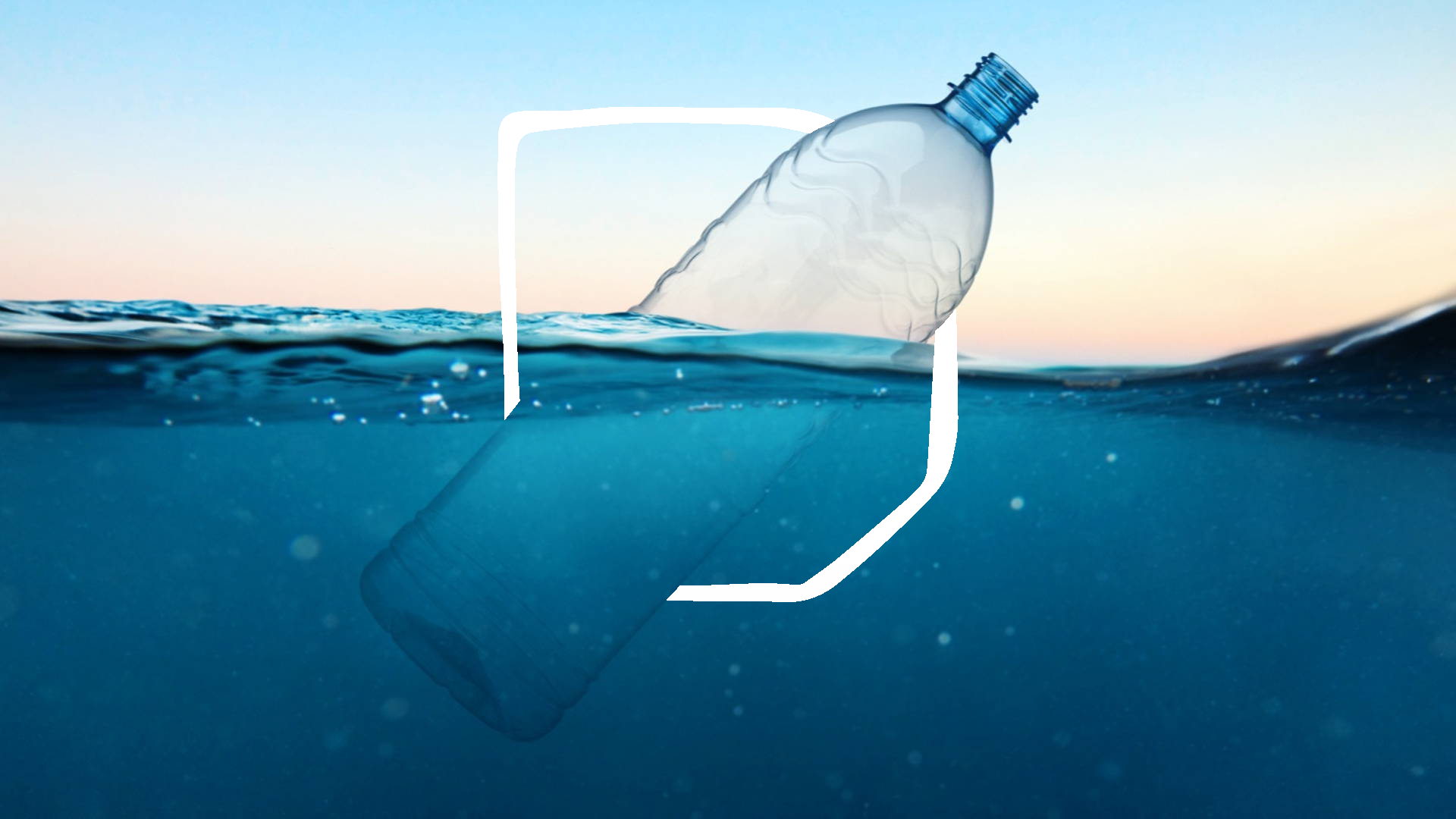

We don’t want to overwhelm you with all the sad and sobering facts about plastic pollution on our planet, but we do need to talk about our plastic problem. Specifically, plastic bottles, but also the dilemma some of the largest beverage manufacturers in the world continue to create for us.

Get unlimited access to latest industry news, 27,000+ articles and case studies.

Have an account? Sign in