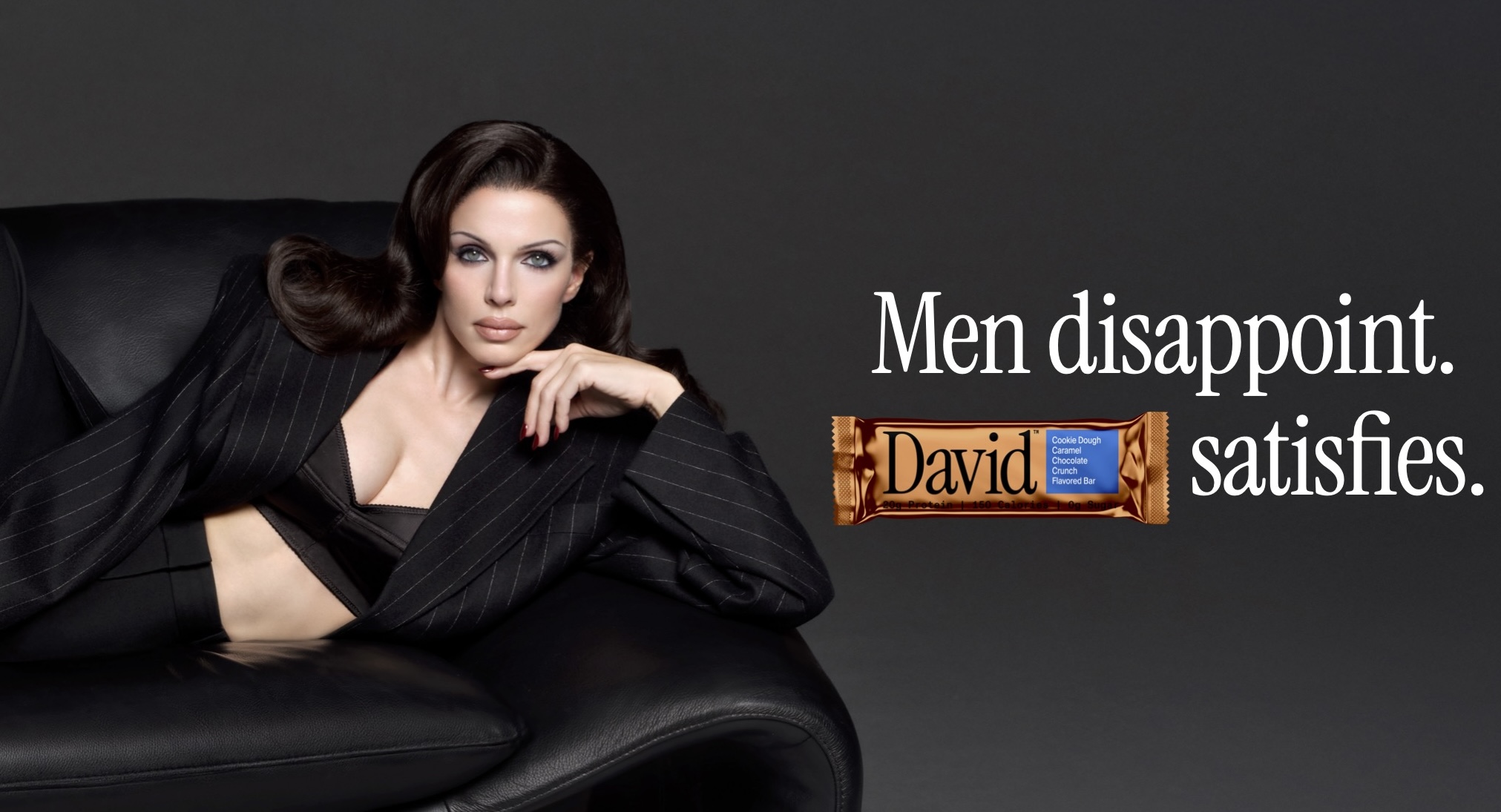

When troops travel to battlefields, sometimes they have to carry their food with them. These meals must provide enough sustenance for the soldier, must be easy to prepare, be as lightweight as possible and packaged to endure the rigors of combat.

It also has to be palatable. If it doesn’t taste good, it can be left uneaten or lower morale.

Prior to modern preservation and refrigeration techniques, troops often suffered from malnutrition, relying on whatever they could pillage. During the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), the French government offered a substantial prize of 12,000 francs to any inventor who could develop an effective and inexpensive way to store large quantities of food. This led Nicolas Appert to create a method for preserving food inside glass jars in 1809, the precursor to canning.