Two months ago, a study revealed that the US recycling rate had dropped to just 5% in 2021. Despite new legislation, such as the introduced (but unpassed) US’ Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act and the Plastics Tax in the UK, which took effect last April, there’s a gaping disconnect between the policies and their intent and real-life impact.

Consumers increasingly demand more environmentally friendly products, while retailers are also putting on pressure, spurred by Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) policies, for more recyclable packaging. So what’s going on? Why are recycling rates so abysmal, and what can brands do to reduce this disconnect to empower consumers?

Of course, design has a pivotal role in tackling this conundrum—and it’s not just about changing materials or introducing limited-edition eco packs.

Tackling Long-Standing Barriers

There’s a critical distinction between recyclable packaging and “packaging designed to be recycled.” While the first refers to the construction and material of the packaging, the second goes much further. It addresses the potential barriers that might prevent successful recycling. In a nutshell, packaging designed to be recycled should be easy and attractive for both brand and consumer.

Easy is about looking at the functionality and communication of the pack through the lens of sustainability. For brands, some of the hugest barriers are any investment in their filling lines or the scalability of innovative technology. Established brands will have multiple filling lines for any product, for example. So good design thinking always needs to look at their situation to recognize that reality and, if possible, work within their current capabilities. That will make it easier for them to implement changes in the short term to meet recycling legislation while helping plan for larger investments in the future that may be necessary to move to more circular sustainability models.

Design indeed has more impact on the consumer experience than the brand/business. Fundamentally the brand has limitations due to its infrastructure, and making massive changes to this in the short term is unrealistic due to the vast sums involved. What we can do though is use what they have in the short term, and get the most out of it, while also planning for the long haul. Design without thought of how a business will implement it will usually fail to get off the ground; to tackle the barrier of investment, we have to make it easier for them by creating achievable stepping stones to a future circular vision.

Kellogg’s, for example, has recently reduced the sizes of its core cereals to make material savings and ensure packs are compact in transit. A simple evolution that will have had little effect on its filling lines but provides an immediate benefit while the brand tackles a longer-term challenge of removing the single-use plastic bag liner. By breaking down a sustainability vision into small, achievable steps, design can help to tackle the barrier of expensive investment.

From a consumer’s point of view, we need to think about the whole process—from picking a product on the shelf or online to making recycling as easy as possible. As humans, we’re inherently lazy. If the act of recycling is difficult or unclear, we’re unlikely to recycle—or even know how to. It is crucial to consider all barriers in the consumer journey. Can your trash be cleaned quickly and easily? Are the material components intuitively separated? Can the materials be conveniently collected from the curbside?

Unlocking New Experiences

Making recycling attractive also applies to both brands and consumers. For the brand, we need to consider cost neutrality, if not lowering costs—making it attractive for the brand to contemplate change. For the consumer, it means that sustainability should not be a compromise. When done correctly, it can unlock exciting new experiences.

Colgate’s new Elixir packaging has reinvented the traditional toothpaste tube as a sleek bottle. Coated with LiquiGlide, a substance that reduces friction and therefore prevents toothpaste from sticking to the sides, it makes getting their toothpaste out easy, but also makes the product ready to recycle after use—much more convenient and pleasant to use.

Elixir’s aesthetic also leans into beauty packaging conventions. It reimagines toothpaste as something worthy of belonging on your bathroom counter rather than hidden away in a cabinet or drawer, driving desirability by tapping into current #shelfie trends and self-care rituals.

The Power of Disruption

Such stand-out is a crucial tool when designing for recycling. Just like the traditional tactics used to sell products, being distinctive visually and tangibly can help sell sustainability and change behaviors. Distinctiveness makes the act of recycling more visible and even more desirable. It creates disruption and encourages conversation. Does this look cool? Do I want to pick it up?

If we want to change the habits a consumer has developed over a lifetime, we need to look beyond those people already on board with sustainability and consider those less engaged. How can we get them to rethink their daily routines?

Ecover was one of the first sustainable disruptors, using in-store refill stations to raise awareness of circular thinking and encouraging consumers to break single-use habits (across more than 700 locations in the UK). More recently, the brand has introduced 100% recycled plastic bottles that stand out on the shelf with their elegant design and even celebrate the slight tint caused by impurities in the plastic. The brand has presented its sustainable philosophy as a cutting-edge, desirable design and positioned it as the modern cleaning brand.

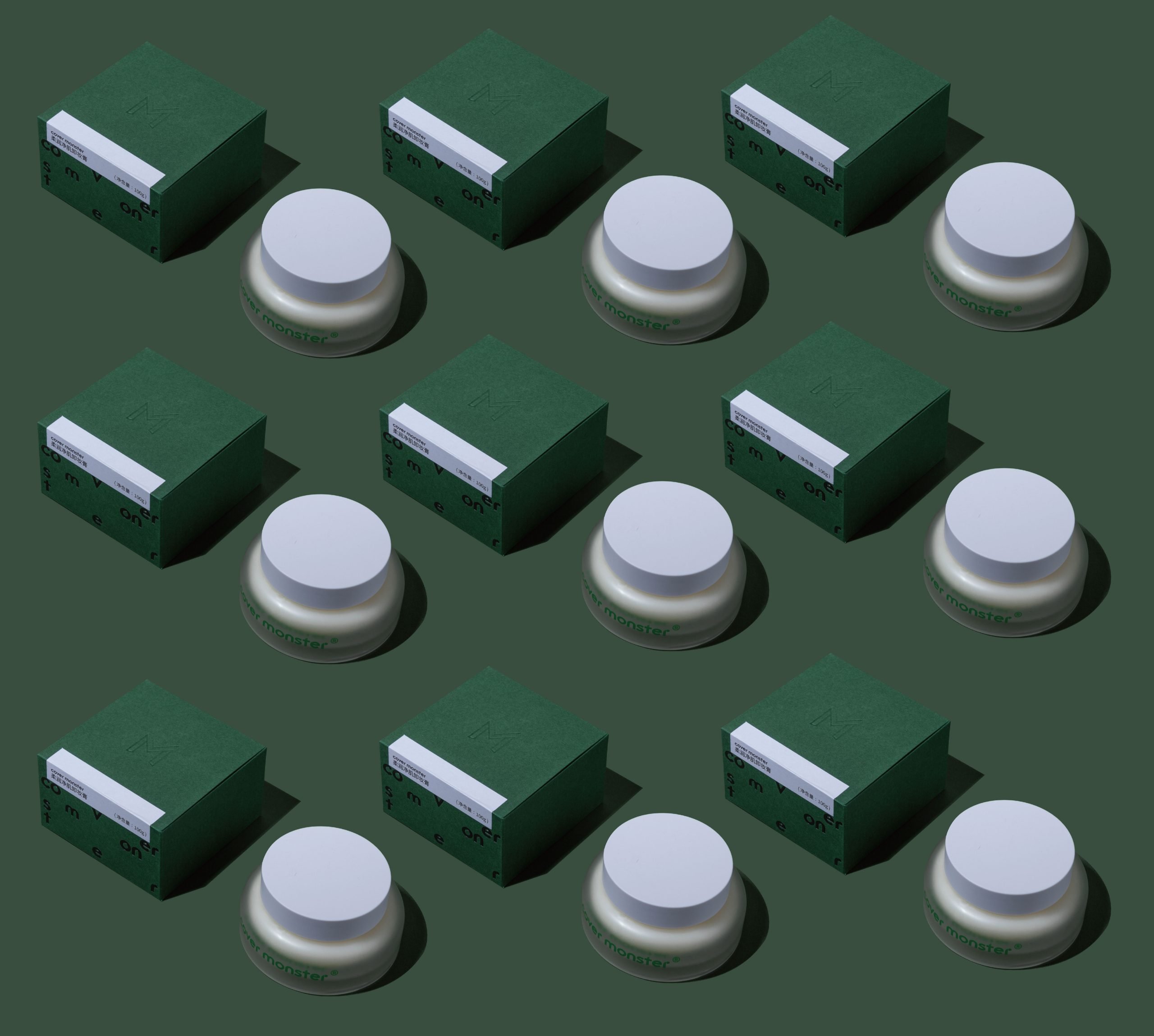

Small, agile direct-to-consumer brands, meanwhile, such as cleaning products Smol or deodorant Wild, are prime examples of new brands doing it well now. They grab attention with desirable packaging that’s convenient and super functional, but by offering new sustainable experiences through innovative and aspirational subscription and refill business models.

And big brands are keeping an eye on this disruptor playbook. Cif and Dove are bringing elements of this thinking to the shopping aisles, for example, with their super concentrate refill bottles that engage consumers in more sustainable rituals. These new packaging formats make an impact on store shelves and make consumers question their everyday actions. Good design should help to break our habits and ‘autopilot’ thinking.

Masters of Scale

That’s not to say that the biggest impact always comes from the biggest innovations. The most effective changes can be small but on a much larger scale.

For example, Coca-Cola recently announced that it will attach all bottle caps to its bottles to ramp up its recyclability by 2024. The tethered cap breaks the habit of throwing the top away or losing it, making it easier for the whole pack to get recycled without requiring extra effort from the consumer.

Tethering bottle caps to bottles seems like a small thing—it doesn’t up the “cool” factor of the product, but that’s the point. If it’s not necessarily driving a behavior change, it doesn’t have to. Changes on such a mass scale will have a significant impact. So, while many direct-to-consumer challenger brands highlight what’s possible, global corporates must keep up to drive momentum.

Breaking wasteful habits and thinking of desirability and disruption (and at scale) is how brands need to think—and what will get the recycling rate moving in the right direction.

Images courtesy of Ecover, Smol, Colgate, Wild, and Kellogg’s.