Want to find out the truth behind some of the best-kept trade secrets? Well, we could tell you, but we’d also have to kill you.

The truth is that some brands and companies very much want their trade secrets to stay hidden. Very few people actually know the formula for Coca-Cola, for instance, and the written recipe sits in a locked vault. Or when it comes to those New York Times Best Sellers lists, it’s very hush-hush how bookseller data gets compiled to create them.

But when it comes to sustainable materials, is it ethical to keep innovative processes secret? Or would the entire packaging industry—and, in turn, the world—benefit from making this information widely available?

Some companies understandably prefer not to divulge the ins and outs of what they produce. The information is proprietary in this case and might include a formula, research, and a design process, among many other things. This kind of trade secret can go so far as to drum up intrigue surrounding a product, and it can provide brands with a competitive edge since no one can confidently make a knock-off.

“There’s an incredible amount of material innovation coming to light at the moment, and it’s changing every element of packaging from alternative paper fibers and bioplastics to inks, coatings, and adhesives,” said Ian Montgomery, founder and creative director of Guacamole Airplane, a design studio that focuses on sustainable packaging. “Intellectual property is important to allow organizations to make back their investments in research and development for these new materials.”

Open-source information, on the other hand, is free for the taking. No one has to play coy when someone asks, “But how did you do it?” Instead, people are more transparent about the processes or materials they use.

Ian credited EcoEnclose and their CEO Saloni Doshi as a gold standard for sustainable suppliers he works with. They’re upfront and honest about the benefits and downsides of every design when partnering with Guacamole Airplane. Ian also mentioned Allbirds as an example of another organization open-sourcing information. “They made the sugarcane-based shoe sole material they developed with Braskem open-source,” he said. “And their goals in doing so were to cement themselves as a leader in the space, but also, by encouraging more brands to use the material, economies of scale will end up driving down material cost. A win-win.”

(Above: Images from Guacamole Airplane’s Sustainable Packaging Supplier Guide.)

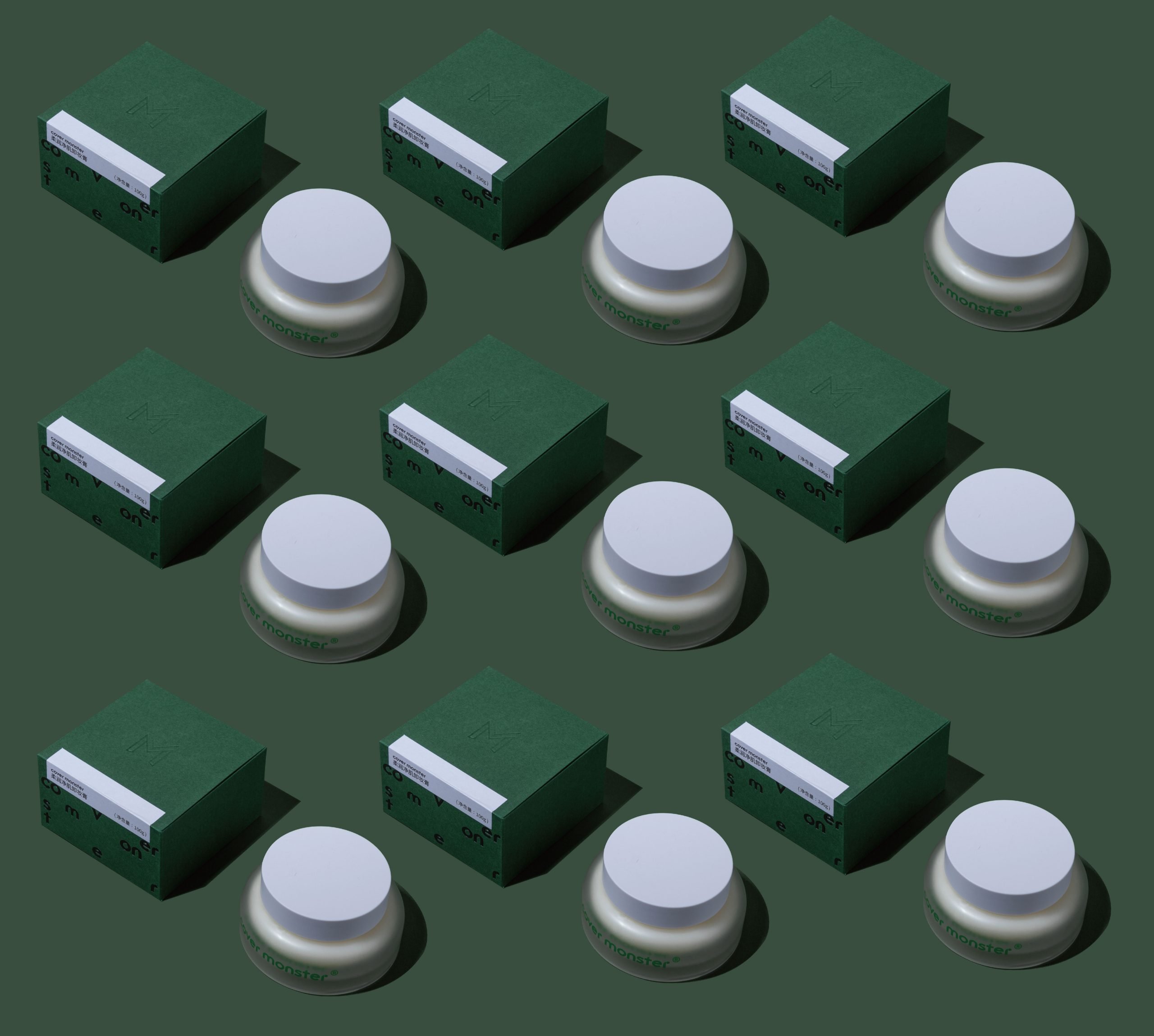

There’s naturally a fear that open-sourcing material might remove a competitive edge. After all, it’s not about who does it first but who does it best, right? While losing a competitive advantage might be a risk, Daniel Lowe, founder and creative director at design studio Someone & Others (the same studio that helped Plus create their no-waste body wash in dissolvable packaging), believes the benefits outweigh the potential downsides.

“If there’s constant development and ideation, it allows for more solutions from different manufacturers or brands, which then allows an agency or client to choose what’s right for the brand rather than potentially retrofitting a brand into a solution.” He also echoed Ian’s point about pricing. “When more people can provide a solution rather than only one, it allows costs to go down and reach the masses quicker and with more ease.”

Isabelle Dahlborg Lidström, Creative Director and Head of Design at Grow, pointed out that there is a lot of trust involved when a brand has something proprietary. “If no information is provided, then the request is that we should trust whoever makes a claim one hundred percent. That is an intangible position to be in, because who polices the police?”

“Some claims need to be made by an independent third party,” she continued. “By having information available as open source, that increases the possibility of the 3rd party being truly independent. In other words, open source replaces the need for blind trust with balanced transparency.”

With all of this in mind, is it ethical to keep trade secrets in sustainable packaging a secret?

Daniel admitted that, while he doesn’t consider it unethical, he does believe “it slows down progress for a better tomorrow.” Branding and creativity, he says, are much more powerful in setting a brand or organization apart than some unique component.

Isabelle said it’s vital to openly discuss materials to speed up the development of more sustainable alternatives and refine current methods. She referred to polypropylene as an example where better communication could potentially make massive improvements.

“There are over 20,000 grades of polypropylene available commercially,” she explained. “All of them are recyclable, but the properties of the materials degrade when they are mixed. To improve the recycling rates for single-use plastics, we need to share what grades get used so that we can harmonize the industries better. That is unlikely to happen without more clear communication.”

Ian added there’s no entirely right or wrong answer and that both sides of the argument are valid. Ultimately, he believes it’s a problem complicated by capitalism. “There is no system that incentivizes innovation and brings people out of poverty like capitalism.” Furthermore, he doesn’t feel that organizations withholding proprietary information about materials is the big hurdle in solving the plastic crisis. Many clients approach Guacamole Airplane after being overwhelmed by all the new plastic alternatives that are available.

“There is probably an over-investment and disproportionately high enthusiasm about material innovation with plastic-free alternatives, whereas less-sexy tools such as infrastructure to sort and recycle flexible films are what’s really needed to counter the plastic crisis,” he said. “Better infrastructure around composting and recycling as well as policies to encourage design for recyclability or compostability are far more important to solving the plastic crisis than any vault of secret information that organizations may or may not have.”

As an admittedly complicated topic, the industry doesn’t have to operate like open-sourcing is an either/or situation. Ecovative, for example, is a mushroom packaging supplier that openly shares the process and raw materials used. But they also don’t specify which breed of mushroom spore they use to get mycelium. Ian said this gets designers and students excited about the material and more likely to advocate for it in their work down the road while also preserving Ecovative’s business model.

In the future of sustainable packaging, it’s entirely possible to preserve the health of a business while advancing sustainable packaging as a whole. The industry is expected to increase by almost $100 billion US dollars by 2028, and consumers are actively seeking out brands with sustainable packaging solutions. Growth is inevitable, and, hopefully, so is helping change the environment for the better—so brands and organizations must determine what role they want to take in that growth and change.