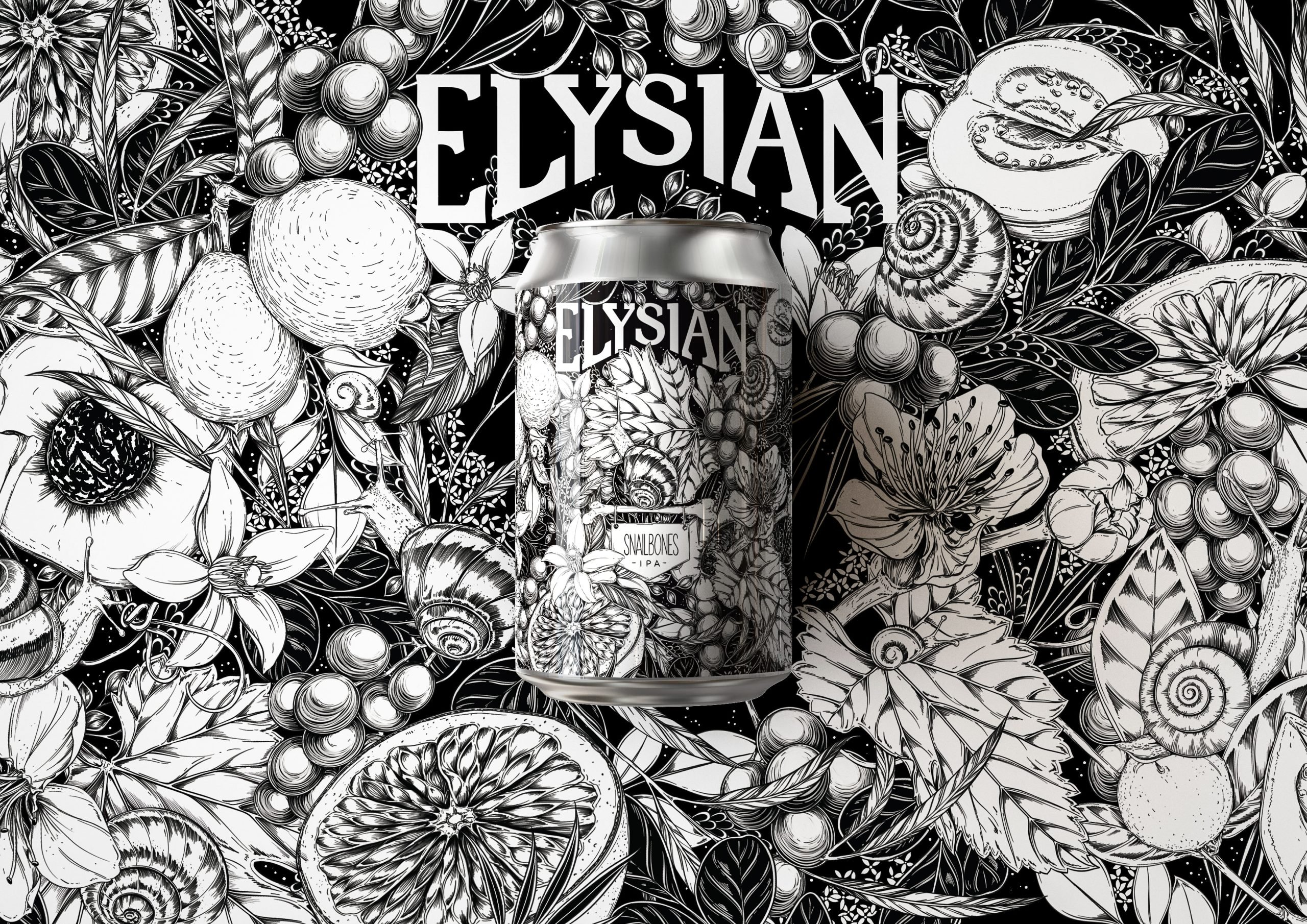

International beer conglomerate Molson Coors recently announced that 99% of their packaging is now sustainable, highlighting several efforts on multiple fronts, including responsible drinking, lessening water waste, repurposing waste, as well as a reduction in packaging. The brand now highlights its latest can carrier made by RingCycles, a six-pack ring that contains a significant percentage of post-consumer plastic and gets manufactured using less energy and water.

But how âsustainableâ are some of these new efforts, and by what measure?

With more consumers considering the environmental impact of a product when making purchasing decisions, firms large and small face pressure to produce goods as sustainably as possible, as well as communicate their green and ethical initiatives.