Youâre blind. Legally speaking. Yes, you can make out basic forms and colors. You can even read a few lines of the newspaper in the proper light. But walking is a challenge. Finding your way to the corner deli is always a bit scary given the blind spots in your line of sight. You bump into more people than you care to admit.

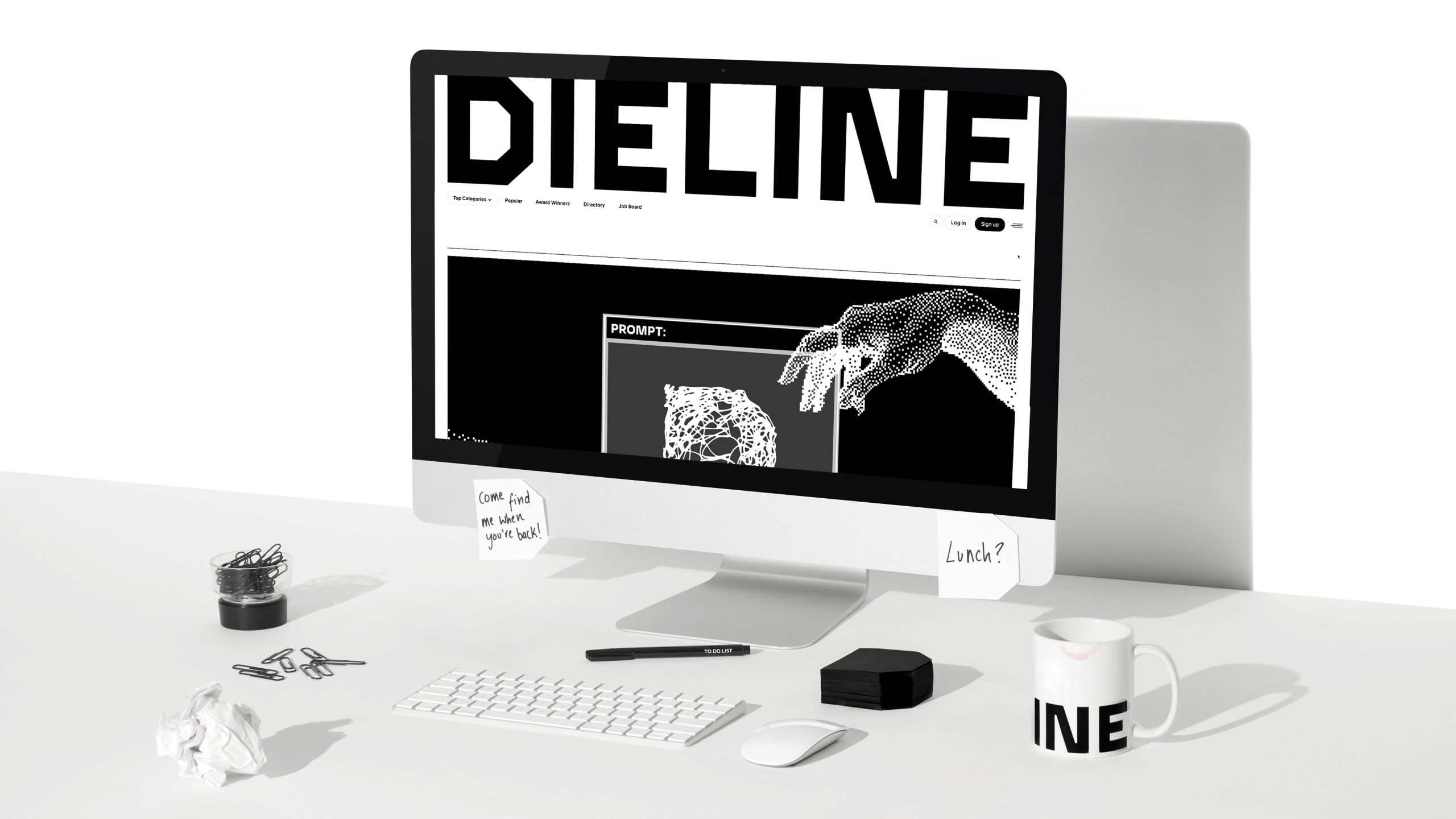

At home, you have a computer but the shapes on the screen blend together very easily. You find yourself squinting and getting lost frequently on a page. Websites are an even bigger issue. The layouts are often complicated, photographs are rarely labeled properly, and itâs nearly impossible to find any clear navigation prompts. Text is often too small, images and colors clash, and thereâs sadly no shortage of bad design all over the internet.

Travel sites are the worst. Inputting the itinerary info is a total puzzle and deciphering the vast array of pop-up windows that follow is simply not an option. Youâll just ask a friend to help with that.